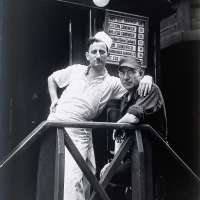

Walker Evans

Ruin of Tabby (Shell) Construction, St. Mary's, Georgia, 1936 From the Full Walker Evans: Selected Photographs Portfolio, 1974

Mount: 14 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches

Walker Evans

Walker Evans Biography Born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1903, photographer Walker Evans took up photography in 1928. Walker Evans is best known for his work for the Farm Security Administration of the U.S. Department of the Interior documenting the effects of The Great Depression. His focus was the government-run resettlement community that housed unemployed West Virginia coal miners. Much of Walker Evans' change to photography from the FSA period in 1935-36 uses the large-format, 8x10-inch camera. His goal was to show Americans how the government was helping fix the myriad of problems associated with poverty during The Great Depression. Setting the government’s purpose for the photographs aside, Evans turned towards his own inner need to document ordinary American life. His palette included iconic photos of old churches, barbershops, roadside fruit stands, and promotional posters. Following his work with the FSA in the summer of 1936, Evans moved south to document stories about tenant farmers in Alabama. At first, it was rejected by Fortune magazine. Undaunted, Evans and his co-author, writer James Agee, published the non-fiction work Let Us Now Praise Famous Men in 1941. The 500 pages of words and images describe what life was like for these people as they lived on the margins of society, barely getting by, yet still trying to eke out a living in the worst of circumstances. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men offered a documentary on The Great Depression while highlighting the autobiographical pathos of Evans, who, as a person of relative privilege, felt compelled as an artist to tell a story that ordinary photojournalists in the urban north would not have touched. Walker Evans said that his goal as a photographer was to make pictures that are 'literate, authoritative, transcendent'. Evans’ photographs are featured in the permanent collections of museums and have been the subject of retrospectives at such institutions as The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Evans died in 1975, two years into the experimental photos he took with the brand-new Polaroid SX-70 camera (with an unlimited supply of film), at the time considered the highest form of technology, with instant photos available just a minute or two after photographing his subjects. His Polaroids were the last photos Evans took after a 50-year career of documenting The Great Depressions, New York City subways, and World War II veterans grappling with the aftermath of the conflict.