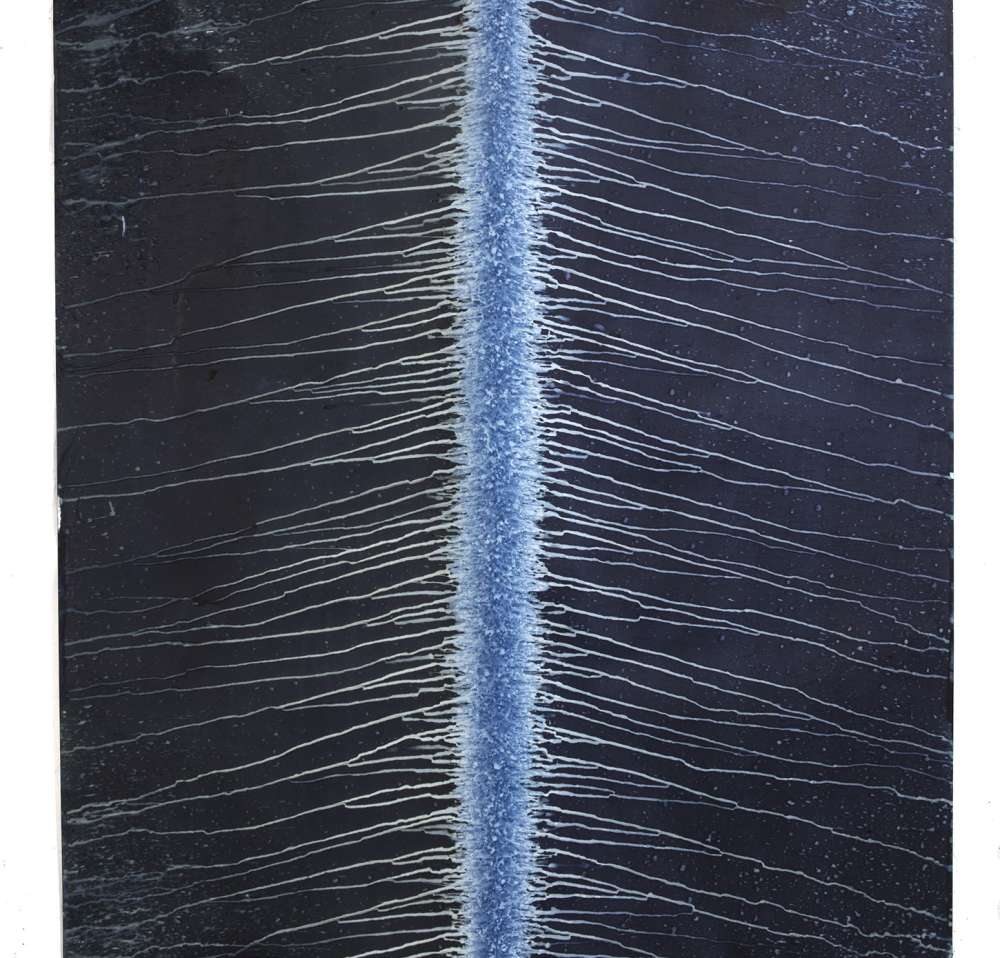

Today, photography’s ubiquity makes it hard to imagine the infancy of the form, when creating just one image was a painstakingly delicate process. In 1843, Anna Atkins, daughter of the prominent British scientist John George Children, began work on her book of photograms (the full edition of which would include over 400 prints) documenting specimens of British algae, what is now considered the first book to be fully illustrated with photography and the first use of photography for scientific documentation. Two exhibitions at the New York Public Library’s Schwarzman Building, “Blue Prints” and “Anna Atkins Refracted,” celebrate this astonishing historical achievement, as well as the legacy of Atkins’s work for contemporary artists.

Exposed to her father’s scientific research and colleagues at a young age, Atkins developed a passion for nature, science, and drawing from life. As an adult, she practiced lithography, watercolor painting, and became enthusiastic about botany, a rare acceptable scientific pursuit for women, becoming a member of the Botanical Society of London shortly after its formation. Atkins’s project grew out of her interest in artistically and accurately documenting the natural world. She began printing around the same time Henry Talbot made public his own development of printed photography and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced his development of daguerreotype photographs. Photographic advancement was in the air, but not in the form we are now familiar with. Atkins’s own method was the cyanotype, today more commonly known as the “blueprint,” developed by her father’s close friend Sir John Herschel in 1842. The process is fairly simple compared with other photographic methods, as it involves only two chemicals—ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide—brushed onto paper, which is then left to dry in the dark, and used as the surface onto which a negative is printed to make a photograph. Alternatively, an object can be placed on the paper to make a photogram. When exposed to sunlight the chemicals bind as a water-insoluble dye, which, when oxidized, gives a cyanotype the deep blue tones it is named for.