BOSTON — Ah, wilderness! It’s our answer to Europe’s cathedrals, our proof of a unique national identity.

Most citizens were first introduced to the wilderness by images. In the early 19th century, Thomas Cole placed the eastern wilderness — his beloved Catskill Mountains — on walls. Later in the century, Carleton Watkins’s 1861 photographs of Yosemite contributed heavily to Lincoln’s decision in 1864 to secure the valley forever “for public use, resort and recreation,” the first time any government anywhere set aside land to benefit the public.

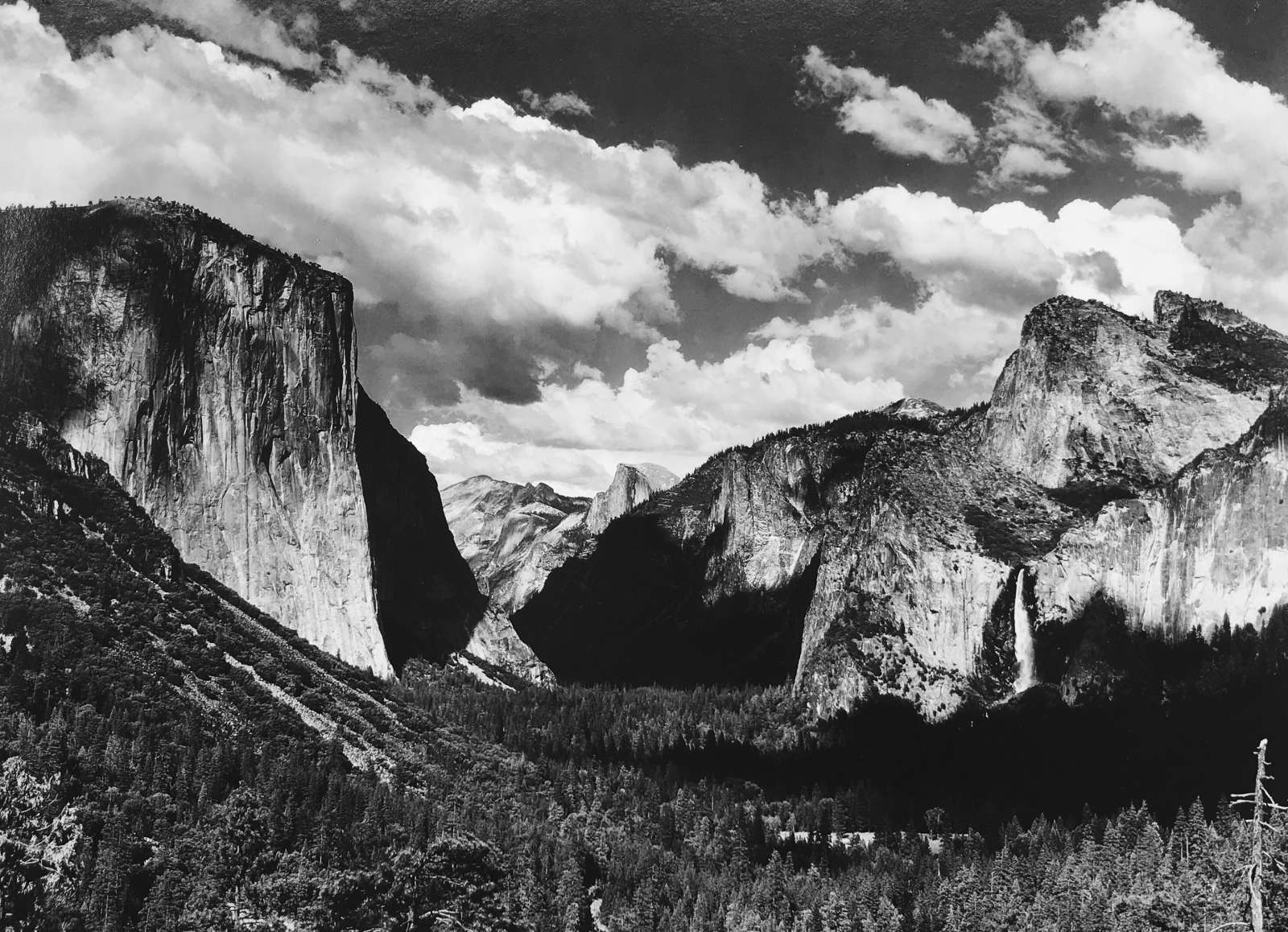

William Henry Jackson’s 1871 photographs of Yellowstone helped persuade Congress to establish the first national park in 1872. Then in the 1930s, Ansel Adams (1902-1984), a staunch conservationist who had grown up near the windswept dunes of Golden Gate Park, lobbied Congress and sent the government a book of his photographs of the southern Sierra Nevada range. They strongly influenced President Franklin Roosevelt’s decision to make the Kings Canyon area a national park.

Late in the 19th century virtually every home had a viewer for 3-D stereographs of a West that looked like a fable. Manifestly — in mind-set as well as mission — the West was our destiny.

And now it is bracing — if perhaps cautionary — to see, close to the moment that the government shutdown has affected many of the national parks, so many noble and challenging images of our country’s heritage starring in “Ansel Adams in Our Time,” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. It is a far-ranging, smartly and instructively installed show of more than 100 of his photographs.

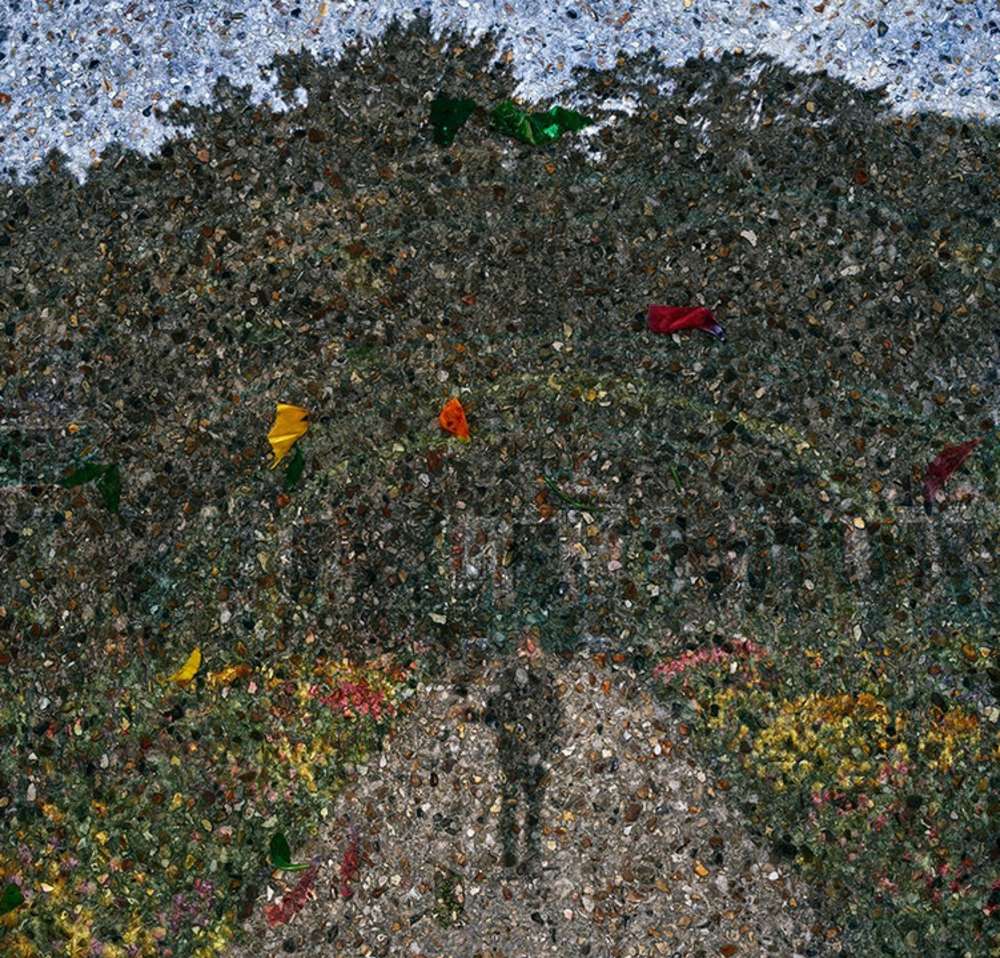

Not a mere retrospective, it also includes about 80 images by 23 contemporary photographers that the curator, Karen Haas, sees as a modern lens on Adams. Although the connections are occasionally a bit tenuous, their addition highlights how Adams, who carried the 19th century’s hymn to America into the 20th century, has remained an inescapable force.